April... I'm writing from a small room down below decks of the Research Vessel the Wecoma Room 13, which on the door says, "(2) scientists." My berth is the upper bunk; the lower bunk belongs to an oceanographer from Australia. He happens to be on watch now, so for the next few hours, I have the rare luxury of some private time. There are 27 people aboard this 180 foot ship, and it is crowded: every possible bit of space contains something, and since this is a research vessel and not a tour boat, research equipment has precedence over "scientists."

The ship right now is rolling back and forth. I was seasick for the first 2 days, but now I'm fine. Being seasick is miserable. Torturous. Everything begins to move and shift. Nothing stays solid. The swell - waves out here in the deep ocean - were larger for the first two days than they are now. Now, today, there is only a small, four-foot swell that is rocking the boat and ruining my handwriting.

I have been on the ship for two weeks now. I work each day twice - from 4 am to 8 am and then again from 4 PM to 8 PM. What I mostly do is simple: I sit for two hours at a computer monitor and control an instrument that is towed behind the ship, then I switch off with my watch partner and go outside, to the stern of the ship and operate the winch that raises and lowers the same instrument. The instrument is a torpedo-shaped probe that has electronic sensors that tell the computer the water temperature, salinity, conductivity, depth, and, most importantly, the direction of the water's current. This probe is lowered and raised continually, over and over.

(Me at a LSI-11/73 making goofy faces)

Everything everyone on board does - the real work - is simple and mindless, as it should be. The experiments being conducted are so sophisticated (there are about 20 mini computers on board this floating laboratory) that human intervention and thought has been made minimal. All we have to do is eat, sleep, and occasionally push buttons or pull levers or lift heavy objects.... except when things go wrong.

So far, in the past week, our only big troubles have been with sharks. The sensors on the raising and lowering probes are delicate, and the probes - long, silvery tubes with fins - look like fish. These hot waters, the water temperature is in the 90's, are full of sharks. The sharks keep trying to eat the sensors, and the sensors keep getting bent and ruined. When I sit at the computer monitor for 2 hours at a time, what I do is look at the probe's signals to make sure that a shark hasn't been chomping on it.

The sharks also follow the boat, swimming behind in the wake. They are ugly things - white-tipped or white finned, that is what someone said their name is - about six feet long with small eyes, a long nose, and a nasty set of teeth. Falling overboard here would be bad. I imagine that no matter how fast the boat could stop, the sharks would be faster.

But it is amazing out here. The water is clear but looks blue like myrtle flowers. We are heading due east, exactly on the equator, since most of the experiments being done are to collect information about the mixing currents at the equator. This morning, while I was outside at 7:30, the sun was rising in front of the boat while the full moon was setting behind us and the three - sun, boat and moon - were in a perfect line.

I spent 3 days in Tahiti waiting for the boat to leave, but this is better. At night, especially, there is a feeling of how isolated we are here. Going to the top deck, out of the glare from the ship's lights, and looking in every direction, there is nothing. Nothing at all except a flat horizon and thousands of stars above.

Where we are is not in, nor even close, to any shipping lanes. In a week, no other boat has come close to us, no other boat has been seen. We are alone here.

So this is it: a kitchen, where the ship's cook prepares 3 huge, delicious meals for all 27 of us each day. A lounge with bean-bags to flop on and with books - mostly cheap paper-backs and a sprinkling of better ones - and a VCR machine and a lot of junky movies. A main work-room stuffed with computers and terminals and instruments. The outer decks where you can sit and stare out at absolute loneliness. And this little, windowless room, which should not be called a room but a 'cabin.' Everything on the ship has a name that is correct and every time I name something it is usually wrong: a wall is a bulkhead, the back of the boat is the stern. The toilet is the head.

Mostly, that is it, but of course there's lots more: engine room, bridge, wet labs, showers, crane room, etc. etc. but I go back and forth between the lounge, the decks, the workroom and this place, 'room 13 (2) Scientists.'

(the main computer room, filled with PDP / LSI-11's, and everything tied down)

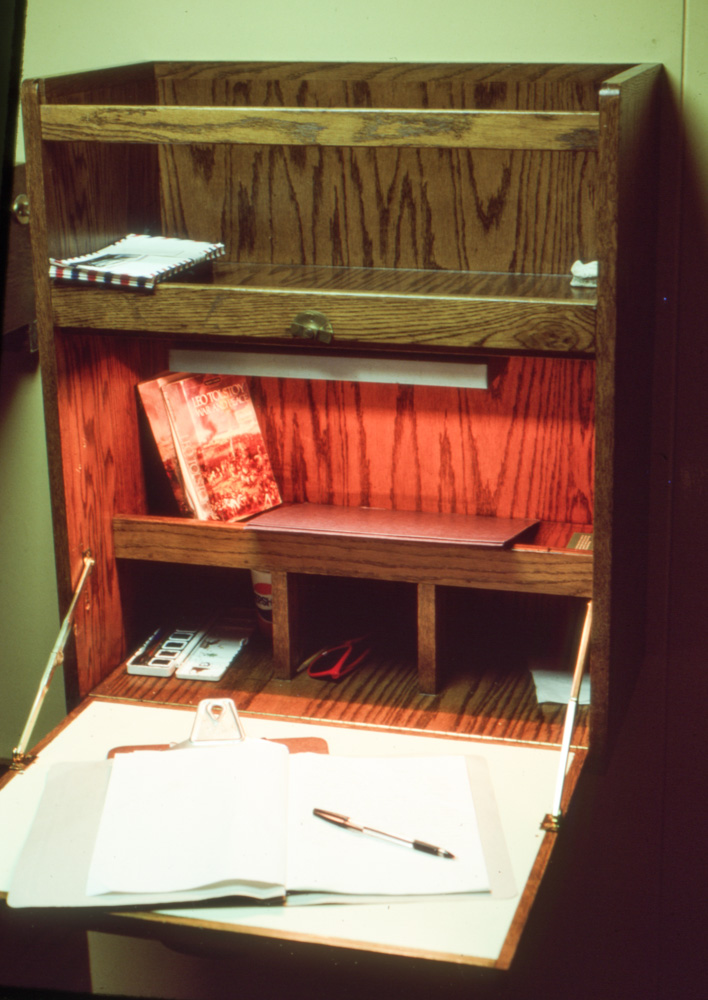

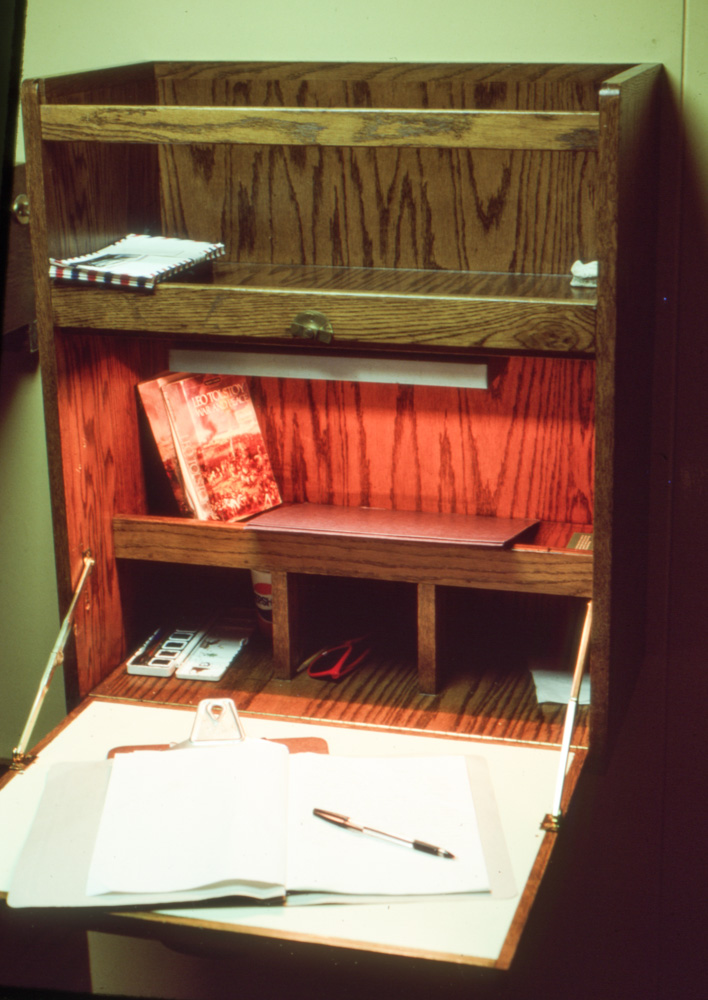

This would quickly become claustrophobic unless you pace yourself and enjoy each, separate ship location. I enjoy all of it, this is my sort of place. Everywhere I look there is something odd and curious. Machines and gadgets are all over, but nothing is junk. Things out here, where there can be sudden and violent movement and salt and wet getting everywhere, are built solid and sealed tight. Things at sea, at least on this good ship, have to work. Everything that can moved is tied down or has good brass latches to be tied down by, and everything fits well. Like this desk, I am writing from a beauty that folds up into the wall when not being used and is constructed out of some sort of exotic hardwood. Harder than oak, but more mysterious, the grain swirls and looks tropical.

(my great desk with watercolors and a copy of War and Peace)

And the people... it is a good mixture. There are 13 scientific people and 14 permanent crew members.

These scientific crew are either Ph.D. types or engineer types (I'm one of the later), but more adventurous than the sorts that I have spent years with in labs and classrooms. These people are here after spending a lot of time preparing their experiments, and now, with data actually being collected at the equator, they are happy and relaxed, something that people in labs rarely are.

The permanent crew members, without exception, are retired Navy men, each with at least 20 years of experience at sea. An oceanographic vessel is a coveted ship to work on, and these permanent crew are, I've been told, the best of sailors. They are rough and heavy, and they like to poke fun at the scientists. These sailors constantly see what they can get away with, how far they can go. Each crew member has at least one tattoo clearly visible - in the heat outside most don't wear shirts - and they pride themselves in their offensive self-imaging as world-wandering, beer-drinking, whoring, son-of-a-bitches - but they aren't really. They jibe us and are insulting only in a game: depending on how each of us takes it makes for defining the scientist-crew relation.

I have been insulted a bit, but seemed to have passed some kind of test. Maybe it was from taking the small, verbal pokes with laughter, and maybe because I took my turn giving back with the best sort of interest: giving back stories and anecdotes. A sailor with a large belly said to me, "You must be one of those hippies with that long hair," I replied, "I sure am, and you must be the fat man at the circus with that belly." He paused, trying to decide how to dislike me, but I kept going, saying, "you ever seen those guys? I went to this circus when I was a kid, and they had this guy who acted the part of the fat man and then later came out as the strong man. He could hold a woman on each hand, even with his arms outstretched. Two trapeze girls, one dressed in red, the other in black." And before he could say anything else, I asked, "So, those tattoos, does each have a story?" He laughed and answered, "Boy, do they," and we've been friends ever since. Before I started writing these notes I was in the galley eating lunch and swapping stories with three crew members. Stories about where tattoos came from, about lost girlfriends, broken down cars, and the mountains in Montana. In mid-story telling time, the cook came over and gave us all extra scoops of ice cream. Ice cream on the equator at sea is acceptance.

It's 2pm now, 14:00 on the clock. The sun is straight overhead, but down here in this air-conditioned space I don't feel how hot it is. I'm sipping a glass of ice water, water that is distilled daily from seawater, and wondering what I'll do to fill the coming two hours before my watch. It's about 100 degrees outside with a good bit of humidity, so it might be wise just to stay sitting here, in this little room, sipping ice water and writing notes. This is the life.

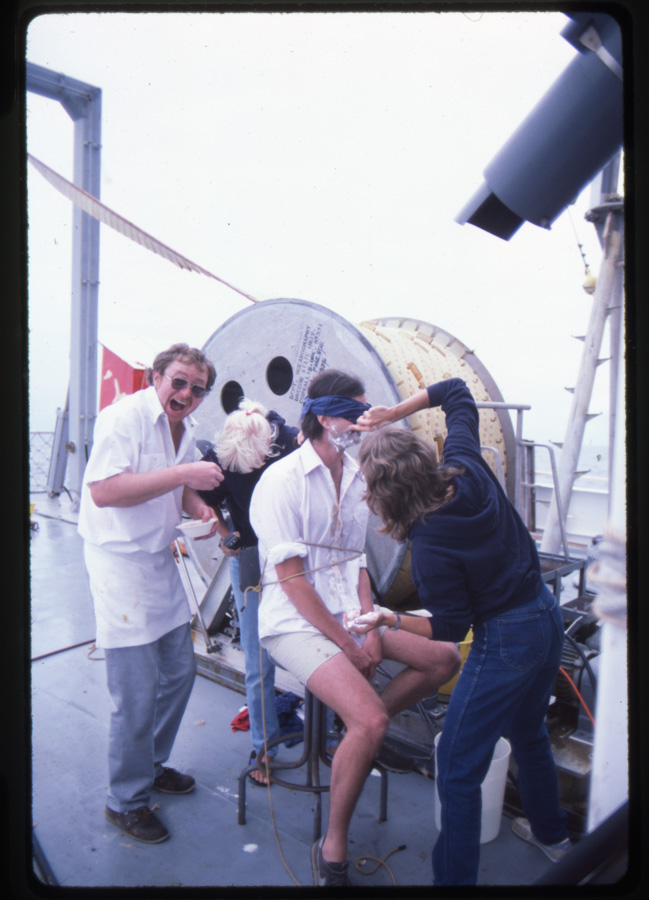

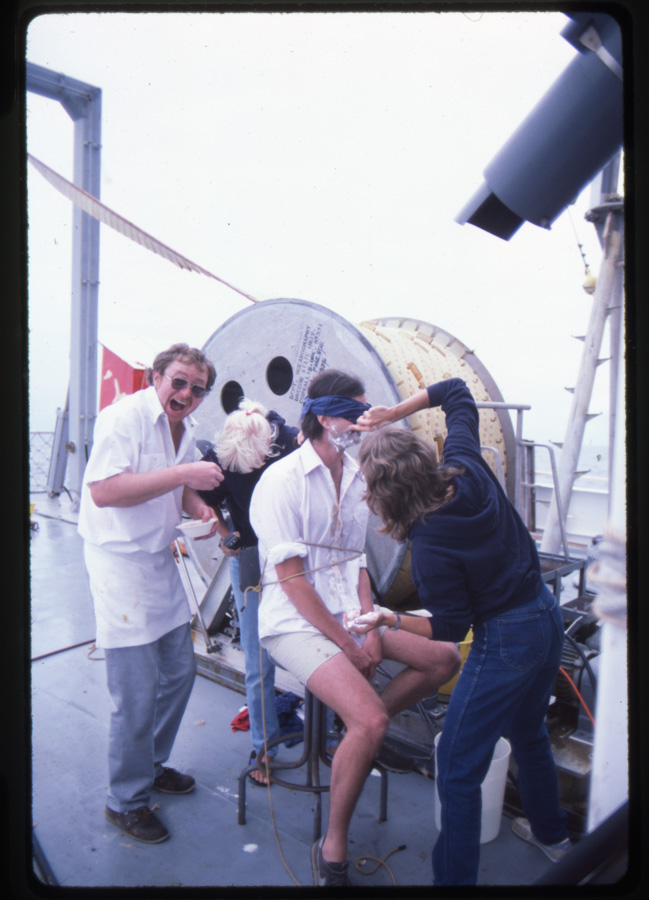

But I did not understand what was coming for me!

(me at the start of a many hour hazzing during shellback initiation which included being tied, blindfolded, thrown into a outdoor storage locker and covered with ranicid cooking grease, then being 'washed off' by being mildly water-boarded -- which I just held my breath for about a minute which was easy for me then -- and ending with -- while still blindfolded and hooded with my hands tied behind my back -- walking a plank and pushed into a large tub of warm sea water, which made me panic, screaming, thinking I was then overboard and swimming with sharks... then there were hands lifting me up, laughter, and the ties and blindfold and hood removed, and I was then a shellback. )

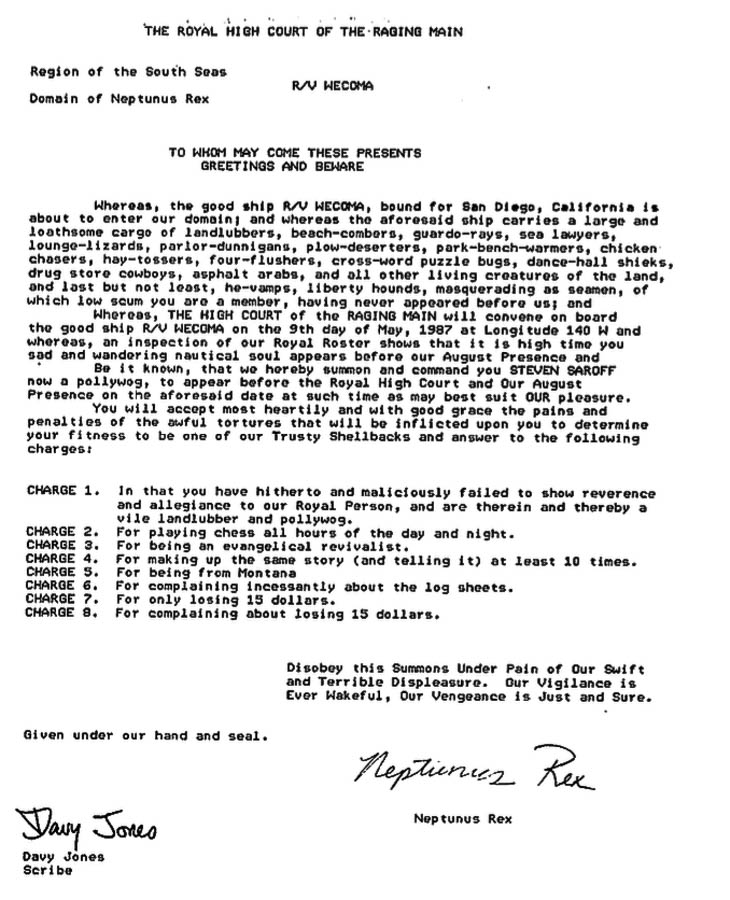

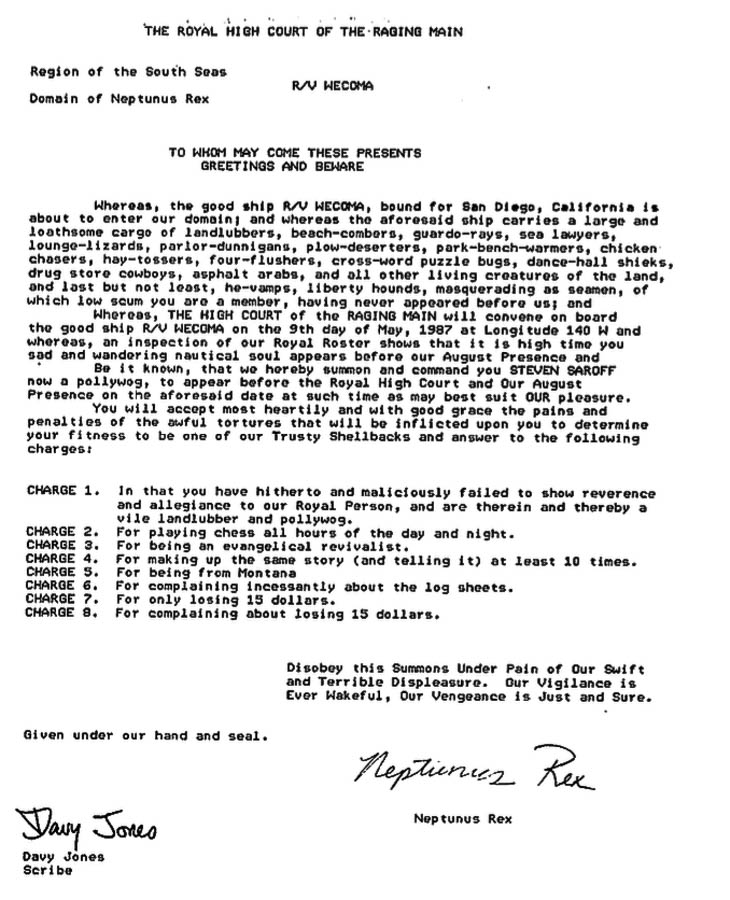

The the list of charges against me that was slid under the door in my berth the day before my hazzing began. Some of the charges against me I did not understand (? an evangilical revivalist ?? ) but others I was certainly guilty of:

Copyright 1987 by Steve Saroff

The ship right now is rolling back and forth. I was seasick for the first 2 days, but now I'm fine. Being seasick is miserable. Torturous. Everything begins to move and shift. Nothing stays solid. The swell - waves out here in the deep ocean - were larger for the first two days than they are now. Now, today, there is only a small, four-foot swell that is rocking the boat and ruining my handwriting.

I have been on the ship for two weeks now. I work each day twice - from 4 am to 8 am and then again from 4 PM to 8 PM. What I mostly do is simple: I sit for two hours at a computer monitor and control an instrument that is towed behind the ship, then I switch off with my watch partner and go outside, to the stern of the ship and operate the winch that raises and lowers the same instrument. The instrument is a torpedo-shaped probe that has electronic sensors that tell the computer the water temperature, salinity, conductivity, depth, and, most importantly, the direction of the water's current. This probe is lowered and raised continually, over and over.

(Me at a LSI-11/73 making goofy faces)

Everything everyone on board does - the real work - is simple and mindless, as it should be. The experiments being conducted are so sophisticated (there are about 20 mini computers on board this floating laboratory) that human intervention and thought has been made minimal. All we have to do is eat, sleep, and occasionally push buttons or pull levers or lift heavy objects.... except when things go wrong.

So far, in the past week, our only big troubles have been with sharks. The sensors on the raising and lowering probes are delicate, and the probes - long, silvery tubes with fins - look like fish. These hot waters, the water temperature is in the 90's, are full of sharks. The sharks keep trying to eat the sensors, and the sensors keep getting bent and ruined. When I sit at the computer monitor for 2 hours at a time, what I do is look at the probe's signals to make sure that a shark hasn't been chomping on it.

The sharks also follow the boat, swimming behind in the wake. They are ugly things - white-tipped or white finned, that is what someone said their name is - about six feet long with small eyes, a long nose, and a nasty set of teeth. Falling overboard here would be bad. I imagine that no matter how fast the boat could stop, the sharks would be faster.

But it is amazing out here. The water is clear but looks blue like myrtle flowers. We are heading due east, exactly on the equator, since most of the experiments being done are to collect information about the mixing currents at the equator. This morning, while I was outside at 7:30, the sun was rising in front of the boat while the full moon was setting behind us and the three - sun, boat and moon - were in a perfect line.

I spent 3 days in Tahiti waiting for the boat to leave, but this is better. At night, especially, there is a feeling of how isolated we are here. Going to the top deck, out of the glare from the ship's lights, and looking in every direction, there is nothing. Nothing at all except a flat horizon and thousands of stars above.

Where we are is not in, nor even close, to any shipping lanes. In a week, no other boat has come close to us, no other boat has been seen. We are alone here.

So this is it: a kitchen, where the ship's cook prepares 3 huge, delicious meals for all 27 of us each day. A lounge with bean-bags to flop on and with books - mostly cheap paper-backs and a sprinkling of better ones - and a VCR machine and a lot of junky movies. A main work-room stuffed with computers and terminals and instruments. The outer decks where you can sit and stare out at absolute loneliness. And this little, windowless room, which should not be called a room but a 'cabin.' Everything on the ship has a name that is correct and every time I name something it is usually wrong: a wall is a bulkhead, the back of the boat is the stern. The toilet is the head.

Mostly, that is it, but of course there's lots more: engine room, bridge, wet labs, showers, crane room, etc. etc. but I go back and forth between the lounge, the decks, the workroom and this place, 'room 13 (2) Scientists.'

(the main computer room, filled with PDP / LSI-11's, and everything tied down)

This would quickly become claustrophobic unless you pace yourself and enjoy each, separate ship location. I enjoy all of it, this is my sort of place. Everywhere I look there is something odd and curious. Machines and gadgets are all over, but nothing is junk. Things out here, where there can be sudden and violent movement and salt and wet getting everywhere, are built solid and sealed tight. Things at sea, at least on this good ship, have to work. Everything that can moved is tied down or has good brass latches to be tied down by, and everything fits well. Like this desk, I am writing from a beauty that folds up into the wall when not being used and is constructed out of some sort of exotic hardwood. Harder than oak, but more mysterious, the grain swirls and looks tropical.

(my great desk with watercolors and a copy of War and Peace)

And the people... it is a good mixture. There are 13 scientific people and 14 permanent crew members.

These scientific crew are either Ph.D. types or engineer types (I'm one of the later), but more adventurous than the sorts that I have spent years with in labs and classrooms. These people are here after spending a lot of time preparing their experiments, and now, with data actually being collected at the equator, they are happy and relaxed, something that people in labs rarely are.

The permanent crew members, without exception, are retired Navy men, each with at least 20 years of experience at sea. An oceanographic vessel is a coveted ship to work on, and these permanent crew are, I've been told, the best of sailors. They are rough and heavy, and they like to poke fun at the scientists. These sailors constantly see what they can get away with, how far they can go. Each crew member has at least one tattoo clearly visible - in the heat outside most don't wear shirts - and they pride themselves in their offensive self-imaging as world-wandering, beer-drinking, whoring, son-of-a-bitches - but they aren't really. They jibe us and are insulting only in a game: depending on how each of us takes it makes for defining the scientist-crew relation.

I have been insulted a bit, but seemed to have passed some kind of test. Maybe it was from taking the small, verbal pokes with laughter, and maybe because I took my turn giving back with the best sort of interest: giving back stories and anecdotes. A sailor with a large belly said to me, "You must be one of those hippies with that long hair," I replied, "I sure am, and you must be the fat man at the circus with that belly." He paused, trying to decide how to dislike me, but I kept going, saying, "you ever seen those guys? I went to this circus when I was a kid, and they had this guy who acted the part of the fat man and then later came out as the strong man. He could hold a woman on each hand, even with his arms outstretched. Two trapeze girls, one dressed in red, the other in black." And before he could say anything else, I asked, "So, those tattoos, does each have a story?" He laughed and answered, "Boy, do they," and we've been friends ever since. Before I started writing these notes I was in the galley eating lunch and swapping stories with three crew members. Stories about where tattoos came from, about lost girlfriends, broken down cars, and the mountains in Montana. In mid-story telling time, the cook came over and gave us all extra scoops of ice cream. Ice cream on the equator at sea is acceptance.

It's 2pm now, 14:00 on the clock. The sun is straight overhead, but down here in this air-conditioned space I don't feel how hot it is. I'm sipping a glass of ice water, water that is distilled daily from seawater, and wondering what I'll do to fill the coming two hours before my watch. It's about 100 degrees outside with a good bit of humidity, so it might be wise just to stay sitting here, in this little room, sipping ice water and writing notes. This is the life.

But I did not understand what was coming for me!

(me at the start of a many hour hazzing during shellback initiation which included being tied, blindfolded, thrown into a outdoor storage locker and covered with ranicid cooking grease, then being 'washed off' by being mildly water-boarded -- which I just held my breath for about a minute which was easy for me then -- and ending with -- while still blindfolded and hooded with my hands tied behind my back -- walking a plank and pushed into a large tub of warm sea water, which made me panic, screaming, thinking I was then overboard and swimming with sharks... then there were hands lifting me up, laughter, and the ties and blindfold and hood removed, and I was then a shellback. )

The the list of charges against me that was slid under the door in my berth the day before my hazzing began. Some of the charges against me I did not understand (? an evangilical revivalist ?? ) but others I was certainly guilty of:

- For playing chess all hours of the day and night. (Guilty)

- For being from Montana. (Guilty)

- For only losing 15 dollars. (In a game of poker - Guilty)

- For complaining about losing 15 dollars. (Guilty)

Copyright 1987 by Steve Saroff

#

Dear Reader, I truly hope some of the moods in my writing reach you. But, if you prefer to listen rather than read, many of these stories and writings are available on Spotify, iTunes, etc., as well as directly on the Montana Voice Podcast

And to readers who want more: the best way to encourage the publication of my next book is for my current books to receive more reviews. If you have read Paper Targets please consider leaving a review of it on Amazon. - Thank you!!!

Most of the stories and essays beneath have been puplished elsewhere, but sometimes I post new work and move out old work.

Fiction:

- Success - a short story

- Letter To My Daughter - a love story in Redbook (A bit about how it was published here)

- Wildhorse Island - another Redbook story

- Boston Girl - a short story set in Missoula.

- Lies - an Enzi story

- Christmas, Seventeen - an Enzi story

- The Long Line of Elk, poetry.

- Paper Targets, the popular novel inspired by true events.

- Back story I of Paper Targets

- Back story II - more of what happened

- PVO - remembering a friend

- Dyslexia, the advantage

- Leaving Home - a rememberance

- Music - another rememberance

- R/V Wecoma, On the route to becoming a shellback

Click here to Contact Steve S. Saroff

Return to Top of Page

Steve S. Saroff — Start-up consultant — Author

(c) 2024 Saroff Corporation

www.saroff.com