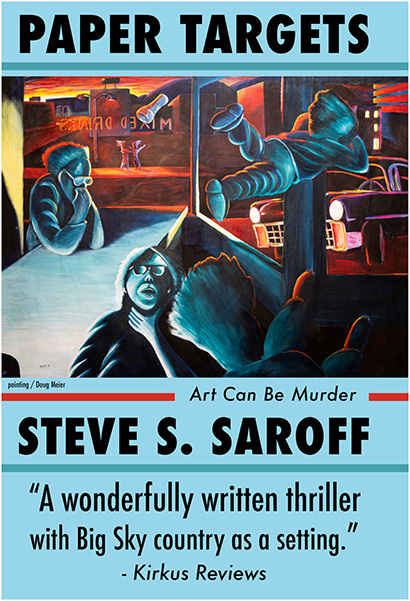

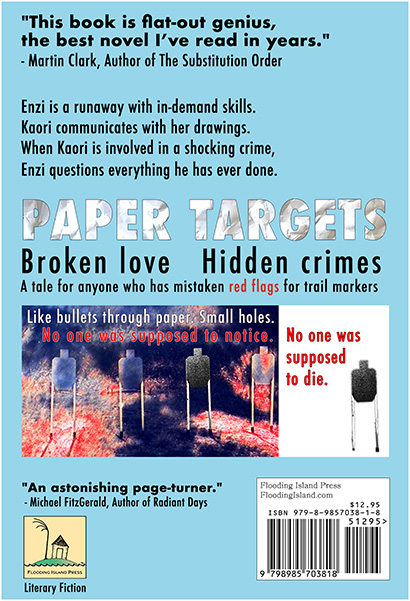

Paper Targets - by Steve S. Saroff

Chapter 1 – HelenSecrets that are shared but still not understood remain secret.

My first secret was that I could not read. And yet my earliest joy was listening to the murmuring of my mother as she read to me. We sat on a couch, a book shared between us, and I remember leaning against her. I also remember trying to touch the words, their shimmering mystery, as she held and guided my hand back and then slowly forth, beneath the lines. This was in a room connected to the garage where my father sometimes spent his evenings drinking and tinkering with his car. I remember looking up and seeing him through the open door. My second secret was that I could feel the sadness that swirled between my parents.

Sometimes, after my mother put the book away, I would go into the garage where my father was. He also guided my hands, helping me lift the heavy wrenches and showing me how they could take apart and put back together broken things.

And so, I grew up with the soft sounds of words and the metal hardness of tools. But as I grew, letters kept flipping, reversing, and tormenting me. When I tried to explain, I st-stuttered. But looking at trees, the clouds, or the cracks on the sidewalks, I saw patterns that did not have to be deciphered or explained. And those patterns flowed into each other. Looking up, through the branching limbs of an oak, into the turbulence of a storming sky, then looking down at the rain splashing at my feet as I walked home from school, I felt connected to what I then had no words for.

I have words now. And as I touch this keyboard, and if you are reading here, then you and I are not so far apart. But my lonely story will share better if I first tell you some of where I came from. Far enough back, all of us must have a connection, a history, to those who struggled and left. It might be great grandparents. Or closer. It could be your father or your mother. Or maybe, like me, it might have been you who had to run.

My parents were immigrants. My father, as a young scientist, was invited to become part of a university, and my mother, a professor of literature, came with him. So I was born in America. But my mother became sick, and she died when I was twelve years old. Then I was alone with my father, who had started to drink as my mother had begun to die.

It was my father then who would wake me each morning before he left for work, not returning until he was drunk, the sky long past dark. I would hear the car tires crunching on the gravel where he parked. I would hear him stumbling into the house. Lights would go on. Sometimes he would sing, though mostly, he was quiet. But other than his not being there, he was not abusive.

He would always check on me -- a few moments, some brief talk. The 'Hey Enzi, how was your day' interactions perhaps made him feel everything was still good. He had a great job in America, and he had a son. We were not hungry. But my days alone, facing the bullies at school who were drawn to stutterers like me, or, conversely, being ignored by teachers who avoided those of us who struggled to read and talk, made me fidget. My inability to read or write, my dy-dyslexia that turned my vision into a forever migraine-aura, and frightened my speech into a st-stutter.

When I wasn't in school, I would walk in the woodlands that divided the suburbs near where we lived. Among the trees and brush -- the White Oaks and the Tulip Poplars, the Sumacs and Dogwoods -- I found something that substituted for friendship. In the green and yellow light that filtered through the summer foliage, or among the shadows of the grass-dry mottled autumn days, patterns and shapes would form and dissolve as I walked. In those narrow strips of neglect behind the houses and the apartment buildings, those places where forgotten kids went to throw rocks and bottles or smoke weed, I fit in by walking by. I wanted to stop, to talk and listen. To learn the names of the other lost kids I saw, but instead, it was enough struggle to learn the names of trees.

Sometimes before going to bed, I would look at my mother's books on the shelves that still lined a hallway in our apartment. Often, I would take a book down, hold it, open it, and remember. The books she had held, the pages she had turned, and I would try to see the words that she had so easily read to me. But, as I tried, the letters would move and swim. Still, I would often bring a book to bed and slowly try to read in the light from my bedside lamp. Migraine sufferers can close their eyes on the confusion of their auras and clench their teeth at the throbbing pain. I did not have any pain, but my auras were constant, and peering through their confused centers, I looked for clarity in my solitude.

But I still tried to read. And I liked best the children's books, with drawings and stories, which my mother had read to me. She would come back then, an arm around me, another holding the book. I remember her deep accent, though she only spoke English with me, "put your hand here," she said, "look at the word and stop trying to see the letters. Look for the shapes." And as most kids start with 'a' then 'b' followed by 'c,' my learning moved slower because I was slow. I had to find words one at a time -- 'sky,' 'rock,' 'tree,' -- among the multitude of drowning letters.

My father, who had studied the molecules of cancer in rooms filled with glassware and centrifuges, had been unable to do anything for my mother as she faded away. Then he had been unable to do anything for me. In his sad despair, maybe like the letters that I struggled to see, he began to drown too. Then after one-too-many DUI's he was fired from his job. Finally, in the self-created legal clockwork of his ruin, I was taken away from him.

There were other schools then, different bullies, more poorly paid teachers, lots of cinder block walls, fewer trees, less sky. And, when I was fourteen, I ran.

I slept against wire fences. I always tried to hide. I stayed out of the cities, and I found jobs further away from everything. I made it through a winter, then another. I lied about my age until I was old enough not to have to lie anymore.

I hitchhiked and found jobs that lasted a few days or a week: picking apples in Washington state, stringing fences on ranches in Wyoming, working and sweating on road crews everywhere. I found the West and nights in bunkhouses, with the sounds of men coughing and drunks talking in their sleep. I found filthy motel rooms with stains on the walls and the forever miles of highways and roads. But I also found the sky, the rivers, and the wind, and I knew that the rooms were only for sleep, that the work was to be able to keep moving. Cities collect the runaways who are afraid of openness. The towns in the West collect the runaways who are afraid of not being able to keep leaving.

But I found something else. Never being able to clearly speak more than the few words needed to get work and rent rooms, in my solitude I picked up books and held newspapers and looked for company in what was printed. And, by doing as my mother had told me, giving up on individual letters and working to see the patterns of complete words, I learned to read. Then, when I had accumulated enough word-shapes, when I had moved away from trying to understand the shifting letters, I was reading full words in the same time that the single ‘a,’ ‘b,’ and ‘c’s’ used to take. And what was in the books came in a fast rush. And the math books I found gave names to the shapes and the numbers I had always seen. But the swirl that I still see in the aura of my periphery is where I have found answers to secrets. In those repetitions that are never the same, math hides in the patterns. And math is what gave me the un-asked-for edge in this world of stainless steel and autonomous machines. The secrets I learned in the patterns that I saw, the patterns that I felt, opened the wide doors to money but also pushed me up against the rusted fringe of too much lonely and bloody greed.

As I drifted, I would look for libraries in college towns and read math books. The best days of my life -- like this memory: the University library in Missoula one September. The fluorescent ceiling lights blinked on and off to warn of its closing in fifteen minutes. I looked up at a clock and realized seven hours had passed. I had been studying the mathematics of automata and trying to find a combination of linear equations that could explain chaos. My thoughts now filled the notebook, but none of those written thoughts were words. They were math symbols, and like Kangi – pictographs of concepts – the symbols carried more meaning than what ‘a,’ ‘b,’ and ‘c’ take pages to explain.

When the library closed, I went outside into the autumn darkness. The air had the woodsmoke tinge of coming coldness. I swung on my pack. I walked across the road that circles the campus. Right there, right next to the library, there was the mountain. Mount Sentinel. I walked partway up, high enough so that I could see the Missoula lights. Up where no one would bother me, I fell asleep in my sleeping bag, with nothing between me and the sky. My dreams had no words. My dreams had only ideas. The following day when I woke up there was an inch of snow on top of me, and I was cold and wet. But I was happy. I walked back down the mountain to the library and books filled with symbols.

I kept drifting, hitchhiking, but when I was eighteen, I bought my first car for three hundred dollars. It was a wreck of a thing, and I expected it only to last a month. Instead, it lasted a bit more than a year and took care of me for thousands of miles. That year, whenever I got any pay, I would buy a few more tools and fix things. I replaced the thermostat. I replaced the alternator. I changed the tires. I fixed the brakes.

The second winter that I had the car, I was working in the northeast corner of Montana, near the Canadian border, on an oil rig.

My job was melting the frozen mud and water from the catwalks beneath the derrick. I did this with steam from a pressurized hose. It was the lowest paid, worst work. The steam screamed against the metal decks and shrouded me in a mist that soaked into my clothes and kept me covered in a thin, crackling glaze of oily ice all day. By that time, I had learned about work clothes. I had good boots. I had heavy gloves. I wore wool covered by denim. That winter, though, was sleet followed by wind, and no matter how much the crew boss yelled, I couldn't keep up with the ice. Then, one morning there was another man there. He stood shivering and stamping his feet as I showed him how to connect the hoses to the steam fittings on the pipes that ran like electrical conduits all over the rig. He wore thin shoes and a nylon bowling jacket. He wore jeans. He had a cotton stocking cap under his hard-hat. He had on a pair of the lousy gloves available in the trailer office next to the time clock. He cursed with each sentence, "The fucking cold. This fucking shit."

We worked all day into the early winter darkness, until the whistle blew. I turned everything off, coiled up the hose, and hung it in a tool closet, but the new man left his lying there, still connected to the steam fitting. Then he climbed off the deck and walked into the office trailer.

I could hear him yelling, "This is fucking shit." Then he came out holding a check for his one day of work.

While getting into my car, he came up, opened my passenger door, and got in the front seat. When I looked at him, he said, "Brother, give me a fucking ride into town. The man in there says to fuck me," and he gestured with his hand to the trailer, "So fuck him." We were about thirty miles outside of Plentywood, with the only thing for miles being the rig. Other workers were getting into their cars and trucks. I'd been on the road then for years. I knew that I didn't like this person. I wanted to tell him to get a ride from someone else, but instead, I looked at how he was shivering, how thin all his clothes were, and I said, "Sure," and we drove off.

I didn't talk, but he kept repeating how "fucked up" the day's work had been and how "fucking cold" he was. Then he started saying how "fucking much" he needed a drink, and how "fucking stupid" I was not to have quit as well, since by quitting, he had gotten paid for his day's work, while I would have to wait until Friday for my paycheck.

He also kept twisting the radio dial back and forth between stations, rolling his window up and down, looking at me like he was waiting for me to start talking and smacking the dashboard in time with the music from the radio. Finally, I asked him where he had come from. He answered and said that he had come down from Calgary, where he had been in jail. He had come into Plentywood the night before, had spent his last money at a bar, and was told that he could get a job in the morning if he showed up at the Conoco station. He said he had been told, "Anyone can get a job if they show up early."

Then he said, more of a demand than a question, "Brother, where are you staying?"

I had a motel room in Plentywood, but I said, "I sleep here, in the car." He answered, "Well fuck that. Drop me off at a bar. Someplace that will cash my check."

Ten miles from town, there was a restaurant on the highway at a crossroad, with a bright neon sign in the window and streetlights showing the empty parking lot. He looked at it as we drove, and as we passed, he said he wanted me to stop and turn around. He said he was hungry and wanted to get some food, "Before I spend all my fucking money in the bar." So I stopped and went back.

After I parked, he rummaged on the floor by his feet and found a sheet of newspaper. I wasn't paying much attention to him. I had told him I didn't want anything, that I would wait to get food at the grocery store in town. After he got out of the car, I thought about driving away, about leaving him there. It had been twelve hours straight of work. My arms were tingling, and my thoughts were not moving fast. I was listening to the radio, and I was feeling the warmth from the heater - with the engine running - parked there, waiting.

Then he was back in the car, startling me, and he was saying, before he had even slammed the door shut, "Brother, get the fuck moving, now."

I pulled back on the highway and started toward town, and he was quiet for nearly a minute until we were well past the restaurant and onto a stretch of the road that was straight and empty. Then he said, "Change of plans. Drive through town. No need to stop at no bar in this fucking place. We’re going over to 'North D' tonight."

I looked at him. He pulled his left hand from his jacket pocket and held a fist-full of cash, maybe a hundred dollars. I stared at the cash, and he looked like he thought I was impressed. He said, "It was fucking too easy. I wrapped my hand in that newspaper, went up to her, and said, 'Fucking blow you fucking away, give me the fucking money,' and she god-damned did. Everything in the register. Check it fucking out," and he waved the money in my face. Then he said, "Brother, it's half yours. Easy money. Fucking half."

I braked hard and pulled over right there, not even a shoulder. I stopped the car. He told me to keep driving. I told him that I didn't want the money. I told him to get out. He said, "This is easy, this is half yours," and he held the cash toward me again. He said, "Fucking drive me to Williston." I said no. He said, "You were out of there fast, man. You are clean, my brother. You get this for being here. For driving," and he waved the hand full of cash toward the east.

I could have done it. I could have driven him to North Dakota, and maybe he would have given me money. Perhaps we would have been parked in front of some bar in Williston, that most western of towns in that most desolate of states, and he would have gotten out. Then I would have driven the 110 miles back to Plentywood. Back to my motel room. Maybe sleep for an hour, then show up again for work. My exhaustion not even noticed because everyone at those winter workplaces was always exhausted or hungover. Instead, I said, "It's not right. It's not our money."

I said this, and then, with a twitch, like I have poked him in the eye, he fidgeted and exploded. He yelled, "Fucking froze all day." Then he reached into his pocket and had a large, folding knife. Open. "Get the fuck out of the car," he said.

I knew right then that he would try to kill me if I didn't get out of the car. I knew this because I saw, in the light from the radio, that he was moving his knife hand back, but more than that, I saw that his eyes were open wide and that his face was smiling. His teeth were all there, white and clenched. He was about to stab me. Then I opened the car door, and I fell backward out onto the road. I kicked up with my feet, and I thought that I somehow must have kicked his arm. Doing this meant that I was okay, that I was not cut. But he slid over fast behind the wheel, and was driving my car away.

I laid there watching the red of the taillights dim until, about half a mile away, they disappeared. I was in darkness. Not even a light in the distance, just a road at night in winter, with no trees, no houses, no people. I rolled onto my back and looked up. There were the stars. A moonless, cloudless night. Stars thick like a blanket. My stars. The stars I had seen from many places. Stars whose names I knew. Stars that were familiar and comforting and which showed me ever richer, ever better patterns. I looked up, and I saw places where I would be happy. I saw mathematics.

I walked the rest of the night. No cars stopped. And in the early morning, I was explaining my story to the police. They asked me over and over to repeat again and again what had happened. Even though no one blamed me, I had then been awake nearly two days. Back in my motel room, I slept hard and solid, and when I woke, I had nothing but my wool and denim clothes that I was wearing. I had no car, no tools. Through the rest of that winter, I stayed there in Plentywood. I went each pre-dawn to the Conoco station and rode with the other daily-work bums into the fields, to different derricks, to the steam, to the ice.

Seasons changed, and I worked in other oil patches and sweated on other summer road crews, and I found more of the less and less. But I also kept studying mathematics, with no idea of why. Then, for a brief, perfect time, I had stability which calmed all the other variables. I thought that my constant had found me. Is it only once in a lifetime, then forever a search for what was lost? Preparing, and working, so that mistakes that ruined the first chance will not be made again?

Wanting what was good. Wanting what is gone. The morning warmth of a clean kitchen, with bread going into the oven. Wanting a garden behind a rented house on the railroad side of town. Talking about good things to do with tomatoes. Pulling weeds from near the young basil plants. Her going to the university, and me working my labor job. Evenings. She with classwork, me with math books. The studying I was doing on my own, not knowing where it would lead.

She would come over and say to me, “Put this away. I will rub your back. Let’s drink beer and dance. Here. In our home.”

It was after another drifting and homeless winter. I had saved and bought another old car. It was a springtime, and I drove to Missoula, the town where I had been before, the town with the library and the mountain. And I found work, and rented a room. Then Helen found me.

Helen. I met her in Maloney’s, an Irish bar on Main Street. A bar with bright lights, Jameson’s whiskey, Guinness beer, and not much else. I was in there after a day of work. She was in there with a group of students, and when she was next to me, ordering a beer, she touched my arm, she said, “Hey.”

Once in a lifetime?

She asked me if she could eat some of the peanuts spread on the bar in front of my beer. She leaned on her elbows. A jean jacket that was a size too large over a white tee shirt. Long, loose hair. High, Irish cheekbones, sad, Irish eyes. She asked me if I was going to the university. I told her no, that I was not a student. She asked me where I was from. I told her that I was not from anywhere anymore. She said, “We all have to be from someplace.”

I was shy, not knowing what to say to her. Not understanding why she was talking to me. Instead of answering her, I asked her where she was from. Then I asked her why she was in Montana. She sat down on the barstool next to me. She said, “I looked at a map, and Montana seemed a good distance from where I was at the time.” Then she asked, “You want to cross the street? You want to dance with me?”

She told me later that she liked my hands, how rough they looked, and that I didn’t remind her of anyone she had ever known. Such a small, uncontrollable thing, and forever then, I was lost. We were dancing in the Top Hat. She was spinning with both her feet in the air. I was holding on to her, my arms around her waist, her arms around my neck. Her hair was across her face and brushing against mine. She smelled like coffee and lilacs. I told her this, and she said that I smelled like dust. She said, “Maybe we fit each other.” Between songs, we were sweating and laughing. We found out each other’s names. I told her that I was not planning on being in town long and was staying at a motel near the river, where I paid for a room a week at a time. She asked me to take her to the room, to show her the river. I told her that the river there was muddy. She said, “Then show me your bed.” I told her that the room’s bed was lumpy and narrow and that I slept in a sleeping bag. “Then show me that,” she said, “get me out of these bars.”

That first night after leaving the Top Hat, I remember walking with Helen down to the Clark Fork River. We were behind the Sweet Rest Motel on Broadway on the edge of downtown. She was drunk, but I was not. She was standing on the point of a large, angular rock, a beer bottle in her hand, saying, “Watch me now.” Then she tried to spin on one foot, like a ballerina. She said, “I can do a pirouette. My mother made me take lessons. Watch.” She spun. She fell. Her hand with the beer bottle did not let go, and the bottle broke in her hand, and the glass cut deep. Not a metaphor, not some fiction. Real blood and a wound that nearly took her hand.

When Helen and I first went to my motel room I had been frightened of her directness. She pulled my shirt as I was unlocking the room’s door. She kissed my neck. When I opened the door and turned on the light, she walked past me, straight to the table where I had my books.

She picked one up, opened it, sat on the bed, and said, “Yuck. I hate math. I thought you weren’t a student?” Not knowing how to explain, I took the book from her and said, “Let’s walk along the river.”

Now she was sitting in the mud, holding her hand, crying. I sat next to her, saying, “It doesn’t look bad,” saying this because in the dark, I couldn’t see much except the mud. However, when I touched her hand, I felt her blood splashing out on me. I stood her up. I walked her to my car. She said she was going to pass out. I opened the back door, and she lay down on the seat, on top of the few changes of clean clothes I had back there. I told her to squeeze the cut hard and drove fast to St. Pat’s.

At the hospital, I parked next to where the ambulances parked. I opened the back door, but Helen couldn’t sit up. She seemed unconscious. There was blood everywhere. I crawled in next to her. I held hard onto her hand and wrist and pulled her to a sitting position. Then I got her outside the car and onto her feet and dragged her into the emergency room.

She had lost a lot of blood, but the doctor said she had probably passed out because she had been so drunk. They took her into a room where they cleaned and sewed her up. The broken bottle had cut an artery and a vein in her palm, but no tendons, no nerves. A nurse brought me a clipboard and asked me for information. I said all I knew was her first name and that I had just met her. The nurse sat down next to me then and said, “Can you wait here and take her home? Do you know if she has medical insurance?”

I reached into my pocket and brought out my wallet. I looked inside, and I said to the nurse, “I have some money. You can have it, but I have no idea who she is.”

The nurse smiled, patted my arm, and told me to put my wallet away. “When she can talk, we’ll find out what we need.”

I spent six hours in the waiting room. A nurse finally came in with Helen. She was pale and had a bandage and splint on her left hand. The nurse gave me a list of instructions about changing the bandage and some prescriptions for medicine. “You need to get her home now,” she said.

I brought Helen back out to my car. It was now daylight. I was supposed to be at work. She sat down in the front seat. I said something about her mother not doing a good job with the ballet lessons. I asked her where she lived, and she told me. I drove her home, stopping first to buy the prescriptions.

She lived in a small house on the north side of town. I parked in front of the house, and she got out, wobbly, still drunk, and drugged. She leaned against the car and said, “Oh my.” So, I got out and went around to help her. When I got to her, she was still leaning against the car and looking at my clothes in the back seat. She said, “Did I do all that?”

“You were bleeding,” I said.

“No kidding,” she said, “I ruined your clothes. I’m so sorry for all of this.”

I got her arm over my shoulders and helped her into the house, helped her lie down on her bed. I put the medicine where she could reach it, got her some water, and told her that I had to go. “I have to see if I still have a job,” I said.

She nodded, said she was sorry again, and I left.

That is how I met Helen. All these years later, these girls with their blood. Helen’s blood long ago, Kaori’s blood soon. And their paint. Helen’s then, and Kaori’s soon... their paint... and their sadness, and their way of showing with no words.

I lost my job. I showed up after being awake all night in the emergency room and got fired for being late. I didn’t care. I went back to the motel room, lay down on the bed, and slept. When I woke up late in the afternoon, I drove to a laundromat and washed the clothes that had been in the back seat. Then I came back to the room and started packing the few things I had left there. I was going to drive to Idaho; I was about to leave again.

I was putting my stuff into the trunk of the car when a car pulled in next to me. It was Helen. Her window rolled down. Her smile. Her sad eyes. Her bandaged left hand.

“Hi,” she said. “I tried to call. They said you checked out. I need to apologize and thank you for taking care of me.”

She stayed in her car. I stayed where I was. I didn’t know what to say, so I said nothing.

“Here,” she said, “I was out of it this morning. Here, take this. You paid for all my drugs.” She was crossing her good right arm over and out the window, holding some cash.

I told her I didn’t care, that it hadn’t been much, but she kept telling me to take it. So, I walked over and stood there, took the cash, and put it in my pocket.

I asked her if she hurt much, and she said she did. I looked at the size of the bandage and asked her how she was going to get along. She answered that she hadn’t figured out yet how she would get dressed. She was wearing the jean jacket from the night before, except that it was draped over her left arm. She was still wearing the white tee shirt that she had on in the bar. But now, it was stained with blood and river mud.

“You took my shoes off,” she said, “I put them back on, but I couldn’t tie the laces. Could you tie them for me?”

She opened the car door, swung her feet out onto the parking lot, and I knelt and tied her shoes, her muddy shoes. Then I stood up and told her I was leaving town.

She said, “But we just met,” and tried to brush the hair out of her face, but she used the bad hand and said, “Ow. Damn, this hurts.”

I asked her if she would miss many classes, and she said she would but it didn’t matter. Then she told me that it was a good thing that she hadn’t injured her right hand.

“You wouldn’t be able to write, then?” I asked.

“No,” she said, “I wouldn’t be able to paint.”

“Do you paint houses?” I asked, not understanding.

“No,” she said, “I’m an art student.”

Blood and paint. I remember how I stood there, in the parking lot of the Sweet Rest, talking for more than an hour as the evening got dark. She asked why I had the textbooks that she had seen the night before. I told her that I read them to look cool. She told me that she didn’t believe me. I told her that I liked math because it was something that I could understand. I told her that sometimes when I worked on problems, it felt the same way as listening to music. She talked about music then, saying that when she drove from Detroit, she liked the AM radio stations that came through at night. She said she liked the way songs would fade away before they were done and that sometimes the static was the best ending.

She said her parents were angry with her for coming to Montana. She said that her father told her not to study art. But, she said, “Why study at all if it isn’t what you want, right?”

I had sat down on the pavement. I was touching her shoelaces, wondering about when I would get up, get in my car, and drive away. Then she said that her hand hurt, that she had to get home and take her pills. I stood up, said it had been nice talking with her, and I started to get into my car. I didn’t know anything.

She almost let me go, but she said, “Wait. We should talk more.”

I stopped and looked at her. It was dark, nothing but flashing neon from the motel’s half-broken sign. She continued, “I’ll need you to help me with my shoes for a few days. Is that okay?”

I parked my car in front of Helen’s house. I helped her with her shoes. I cut the stained shirt off of her with scissors, her bandaged arm resting on my shoulder, me trembling, her saying, “I couldn’t do this myself.”

I helped her on with another shirt. I buttoned it for her. She asked me to light a candle, and she turned off the lamps. Then she swallowed pills and drank from a bottle of wine. She lay down. I got my sleeping bag from the back seat of my car. I came back into her room. I lay down on the floor next to her bed. She moved to the bed’s edge so that we could see each other. She said that I didn’t have to sleep on the floor. I told her that I wanted to. She asked me why, and I told her that I am comfortable on the floor. She yanked all the blankets off her bed then lay on the floor next to me.

I didn’t know where to put my arms. I didn’t know how to lie next to someone. Helen said, “Here, come here,” and with her good hand, she pulled me until I was wrapped about her, both of us on our sides facing each other. She whispered, “Talk to me.”

I wanted to tell her about trout from the Yellowstone River caught with a piece of string, a hook, and grasshoppers. I wanted her to understand the fires made from river driftwood and all the stars in the perfect sky. Instead, I said, “I don’t know, I don’t know, how, how, to talk,” I said, “I don’t know,” I said, “I don’t know where to begin,” I said, “I don’t know anyone, I don’t know anyone,” all this in a stammer, a nervous and shy voice.

She nodded, brushing her head against mine. She whispered, “I don’t know anyone either. No one knows me. Tell me things.”

That night, that first night with Helen, I told her about how I remembered names of rivers, all the rivers I had slept next to. “Tell me,” she said, and she fell asleep as I strung together names, moving from the east to the west, Shenandoah, Susquehanna, Missouri, Wind River, Columbia.

I found another job, pushing a vacuum cleaner, emptying trashcans, and doing the other things that a janitor does.

For a while, I kept sleeping on her floor. There was no rush, and I eventually started sleeping in her bed. I would sometimes wake in the night and listen to her breathing next to me. I would wake and feel her arms around me. In the mornings, she would get out of bed and open the windows. That spring sunlight, the scents from the flowering trees in her backyard, all of it pouring in.

It had been a month from the night she cut her hand. The bandages were gone. The stitches were out. She told me that I was not camping now. She said that I was living with her. She told me that I didn’t have to keep everything I owned in my car.

She went to classes, painted, and pulled me into a place I had never been before. A place with no struggle. We were both sitting cross-legged on her bed. She reached and touched my hands and leaned forward so that all her hair was spilling into her lap. She wanted to know what I would do with my life. She said that I couldn’t only be a janitor. I asked her why not. She told me that I must be more. I asked her again why, and she stared at me.

I didn’t get it then. The hint of what was coming. Instead, all I cared about was how every afternoon, leaving work, I would be happy. I would be coming back to Helen’s house to share with her.

She bought me presents. A bottle of Spanish olives. Bottles of wine. I also brought her things. Loaves of bread from the local bakery. Flowers from the sides of mountains: Shooting Stars and Lupine, Arrow Leaf, and Larkspur. In the evenings, she would come home from classes and put the flowers in a vase. I would light the candles along the window ledge, the candles on the table, the candles near the bath. She would turn off all the lights and paint. Canvasses leaning against the walls, Helen sitting cross-legged in front of them, a long brush in her hand, the colors muted and orange in the dim light. I would soak in the tub - the grit of my day’s work coming out of my pores - until she would say, “Enzi, come here and tell me what you think.” I would bring one of the candles and sit next to her, moving the flame close enough to see brightness in the wet paint.

She also gave me warmth and touch two and often three times a day. She’d pull her shirt off and tug at my hands. Me barely into the place, the door hardly closed. “Let me wash first,” I said. She smiled, then unbuttoned her jeans and asked, “Why?”

And in the dark too. Me still so close to the road, my solitary nightmares coming at four in the morning. Gasping, awake, I think I am lying by some highway. I’m so young that the barking dogs are terror, so young that I’m hiding from police, so young that I am scared of the older bums who will beat and rob me. It is raining hard; I’m soaked and cold. But it’s only sweat, and the barking dogs are chained down the street, and I’m not a runaway. Instead, I am lying next to a beautiful woman who has told me, “Wake me whenever you want.” I am warm and safe, and I reach across the bed’s darkness and hold her, my heartbeat going from panic to peace. She calms me, she tells me I am dreaming. She puts her mouth against my ear. She tells me how good things are. She tells me how happy she is. I fall back to sleep, listening in the dark to the whispered plans of our shared life. I wanted nothing else. There should have been nothing else.

I wanted to grow with her. I would meet her parents and impress them with my devotion; this was the plan. We were drunk in the kitchen. Drinking wine from the bottle that we were passing back and forth. She invited friends from her art classes, and it was a simple party. Then she said, “I’ll say, Dad, meet Enzi, he v-v-vacuums,” and all the fun evaporated because she was laughing and her friends were laughing, and it was hilarious to them.

... end of Chapter One.

Free Review Copies: Are you an author? Do you write book reviews on social media? Are you in a book club? Do you work at a bookstore or a library? Ask for a free review copy of Paper Targets by sending email to the publisher: info (at) floodingIsland (dot) com

Click here to Contact Steve S. Saroff

Return to Top of Page

Steve S. Saroff — Start-up consultant — Author

(c) 2024 Saroff Corporation

www.saroff.com